In the Beginning, There Were Bandaids

I stayed in denial about Mom's "condition" as long as I could

(if you listen closely toward the end of the recording, you’ll chatting Mom, chatting with the many invisible friends who hang out in her room).

In the beginning, she told anyone who would listen (except me) that she had Alzheimer’s. “Hi, my name is Elayne. I have Alzheimers.” Some doctor, somewhere, before I’d taken over documenting everything, had used the word in conversation and she latched on to it.

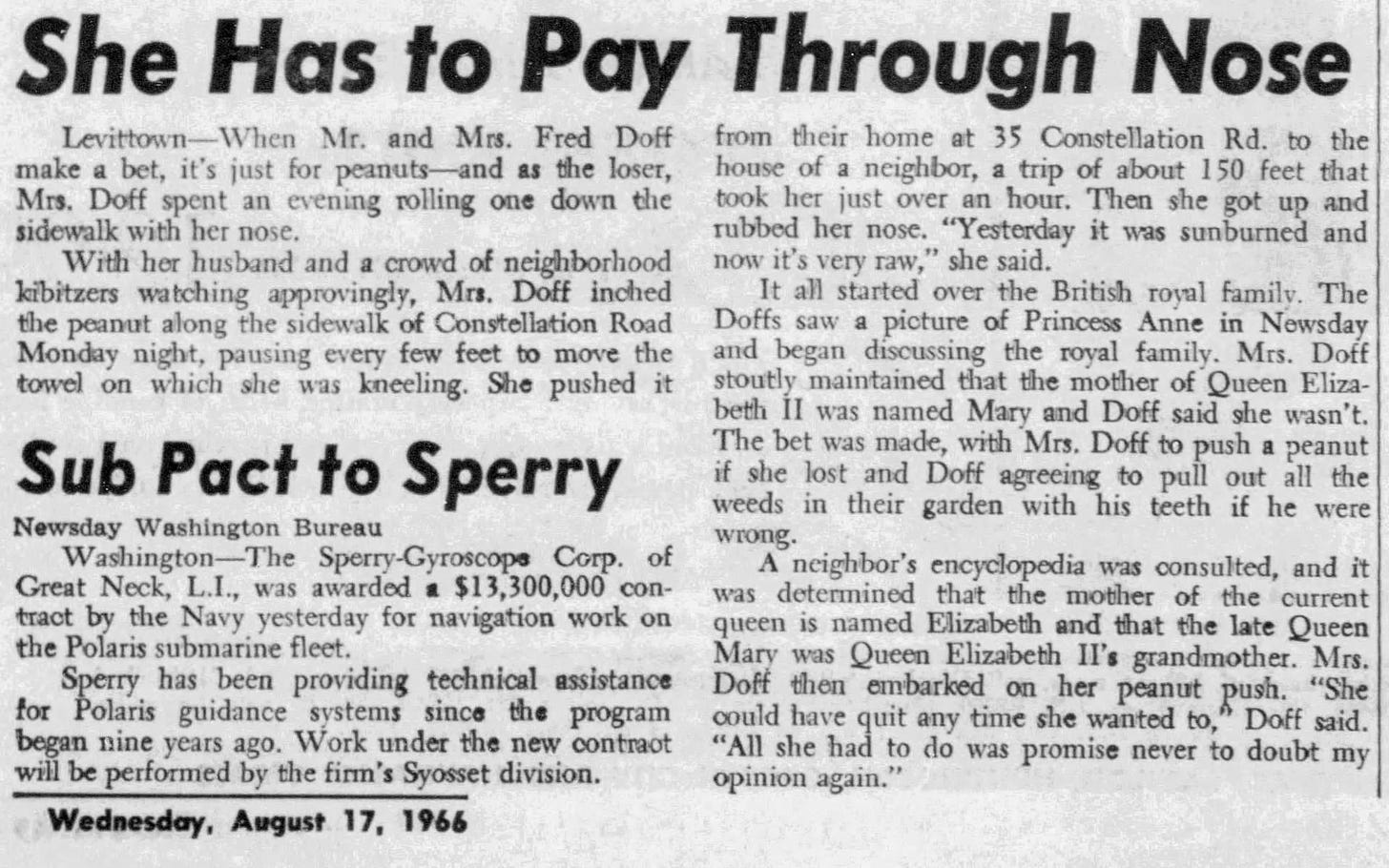

You have to understand, Ma had been kinda wacky my whole life. There was the time she lost her wallet and we found it on a shelf in the refrigerator. She thought nothing of pushing a peanut down the street with her nose as penalty for losing a bet. The local newspapers picked it up and the wire services spread it nationwide as a human interest story. That was my mother.

This was also my mother.

When she couldn’t walk a straight line, pinballing her way down the hall on the way to the elevator, bouncing off a wall now and then, I thought it was cute and called her Wobbles.

What she had, at that time, was mild cognitive impairment (MCI). I didn’t know that yet, and I hadn’t even heard of that.

I accused her of quitting. Being lazy. I didn’t believe there was anything wrong that trying harder couldn’t fix; isn’t that what I’d been told most of my life?1

I shook her. Try harder, Ma!

I labeled things: her radio was covered in those colored sticky dots with arrows and words like: PUSH, ON, RADIO. I lined her pill box with brightly colored foil, so the pills would be more visible,2 and filled it myself every week.

Bandaids. I was applying bandaids to her life. Neither of us were ready for her to stop being the independant woman she’d been all my life.

So, you can see how it was hard for me to differentiate what was Ma, and what was MCI or the myriad smaller things that mark the beginning of the dementia journey. But, somewhere in her, she knew something wasn’t right. Something wasn’t working the way it was supposed to work, the way it used to work.

“Hi, I’m Elayne, I have Alzheimers.”

It wasn’t true, yet, but I guess it was a way for her to understand what was happening, something to point a finger at and say, “See, this is why…”

She forgot syrup, simply forgot it existed. She told me black strap molasses went on pancakes, used spiced apple cider for dry cereal when she ran out of milk. The silverware drawer became “the place where we keep the things we use to eat.” A bookkeeper her entire life who supported the family and managed the family business and all the money, I was finding unopened and overdue bills, and others that had been paid multiple times.

I took the finances out of her hands, which put us both at ease.

Periodically, I’d get the equivalent of a butt dial as she struggled to turn on the television–pointing the cordless phone at it and pressing random buttons, then trying to call me using the television remote, which didn’t work either. Eventually she’d reach me using her cell phone, and tell me both the television and the phones were out of service.

🤦♀️ 🤷♀️

Never what you’d call a driver, everyone had always been at least a little bit afraid to drive with her. She’d put herself in the center of the lane, rather than the whole car; it’s possible that she holds the world record for the most side view mirrors knocked off the parked cars of complete strangers. I’d been her navigator since I was old enough to see over the dashboard because she’s never, ever had a sense of direction. We could get her to drive right through her own street and never realize it unless she actually passed the house. She fell asleep at the movies if someone didn’t feed her M&Ms every few minutes, so it wasn’t all that surprising when she’d fall asleep at a red light. Or heavy traffic. But, after she’d sat in the parking lot of the supermarket, unable to remember how to start the car until a stranger helped her. After a light post suddenly moved into her path. After she stopped in the middle of a very busy intersection trying to remember whether to turn here as other cars speed around and at her, honking, confusing her even more. After all that, I finally took the car keys away.

She was trying harder, though. She’d always been a list maker, there was the Rolodex card3 from my wild years. Now, her lousy handwriting inching toward illegible, her notes were incomplete–a word (coffee cup) or phrase (ask Sybil) or series of numbers, scattered around the house or in her purse with no way to identify what they meant or referred to.

She kept labels of foods she (or the cats) liked, and of those she (or the cats) didn’t. That system made sense, unfortunately she stopped being able to remember which pile was which.

But I didn’t really know4 until I came in one day and she wasn’t wearing her teeth. Outside of surgeons and the original dentist who created her dentures, no one had ever seen Ma without her teeth. Until now.

I’d promised I’d never put her in a home. I’d promised that light years ago, when her own grandfather was put into a nursing home.

Then she stopped recognizing and responding to the smoke alarm and neighbors started checking on her whenever they heard it from her apartment.5 She melted the radio I’d mounted under the kitchen cabinets.6 We’d been campers. I reminded her about the relationship between wood and open flames. When she scorched the kitchen cabinets a second time, I threw out all the candles and replaced them with the electronic ones.

But, it was all just more Bandaids. She couldn’t live on her own anymore. And I was not about to move back to Long Island.7

More on my effed up childhood some other time, some other place.

We hadn’t found out about the macular degeneration yet, either.

Well, okay, I guess here’s a little peek into the above mentioned effed up life.

More precisely, this was the moment I had to let go of any denial I’d been hanging on to.

She’d moved into the bedroom to play on the computer and get away from “that annoying noise.”

She loved candles, but wanted them “out of the way”

aka The Scene of the Crime aka My Effed Up Childhood aka The Lost Years

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Long Goodbye : Dementia Caregiving & Other Stories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.